Tai Chi or Taiji is short for Taijiquan, Chinese health fitness. It is now popular all over the world. It is a combination of a Chinese martial art with Chinese breath training (Tu Na — a special breath training program for health), energy flow guidance (Dao Yin — using the mind to guide the Qi circulation), and meditation progress. Taiji indeed is a kind of traditional Chinese Yangshengshu (a mind–body harmony technique for health improvement and longevity), an important part of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

From a Western point of view, Taiji can best be described as a moving form of Yoga and meditation combined. Originally used for the purposes of martial arts, the slow, graceful movements, however, also reflect the natural movements of animals and birds, as symbols or “pictures,” which were designed to focus the mind and breathing through the execution of a complex series of forms.

As the forms are practiced in slow but continual fluidic movements, breathing is regulated as an integral part of this flowing meditation while the muscles and joints are in constant calculated motion. The effect produces a sedative state directly on the central nervous system (CNS), which in turn helps to stimulate and improve upon other body systems. It is calming and destressing, the movements themselves becoming physical poetry to a meditative dance process.

When practiced properly, Qi energy is increased, and one often feels a tingling of fingers and toes, and a warming-up of the body. The mind becomes clear, and relaxed. The movements give practically a means of motor control, balance coordination, and can help posture and loosen tight muscles.

There are various schools or styles of Taiji: the Chen, Yang, Wu, Sun, and Hao styles. In 1956, Simplified Taiji was compiled to address the above problems; it is also known as the Beijing Style. It is composed of 24 forms (every form including several movements), mostly from the traditional Yang Style 108-form. Simplified Taiji was the result of many Taiji masters working toward standardizing and simplifying Taiji, and focusing on promoting health exercise. One of the most important aspects of Simplified Taiji is that even though the 24 postures of Taiji constitute a simplified version, it is still a “traditional” sequence with the original martial art applications in every movement. In 1979, the Chinese State Physical Education and Sports Committee again commissioned changes. This time the new Taiji version is composed of 48 forms (postures) which consist of the best and strongest points from the Chen, Yang and Wu styles. Currently the Chinese government hopes to popularize it in competitive sport areas such as the Olympics.

Taiji was popular from the 19th century in China as one style of martial art and slowly transferred to Western countries. In the modern world, the main purpose is no longer for fighting but just for health fitness, disease prevention, and therapy. During the last 30 years, Taiji has spread throughout the world, propagated by immigrant populations and the opening-up of China from the mid-1970s. Now, all of those traditional disciplines of Acupuncture, herbal remedies, and Qigong therapies are regaining respect and public interest as they gradually obtain support from modern scientific studies.

It is estimated that there are a dozen million people of all ages practicing Taiji in China. It is regulated and organized by the Chinese National Sports Association. There are national “instructor” exams and coaching seminars as well as organized competitions within individual family styles. Taiji is also one of the official competition events in the larger national and international martial arts competitions, and has been proposed as a competition event to the International Olympic Committee.

The History and Philosophy of Tai Chi

There are some legends about the early history of Taiji. It is difficult to produce a completely unified history about the origin of Taiji, because the secret of Taiji was kept within the individual families for many generations before it was taught to the public. There are missing written records as well. Most people believed that Taiji was developed into the present style by martial art masters during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties.

The most recent research shows solid evidence: the earliest “Taiji 13 Forms for Health Cultivation” was created at Qianzai Temple in Tang village by Chen Yu-Ting (1600–) from Chen Jiaguo village, Wen County, and Li Yan (1606–1643) from Tang village, Bai County, Henan Province of China (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji). Wang Zong-Yue (1750–) learned Taiji from Li He-Lin in Tang village. He wrote a text entitled Taijiquan Lun, which is the most important part of a collection of classical writings that form the guidelines for all styles of Taiji.

The other legend says that the credit for formalizing the soft-style series of exercises into a unified whole belongs to a Taoist Priest, Zhang (or Chang) San-Feng (1270–1364). He lived as a recluse on Mount Wu-Tang in Hebei Province of China. As the legend goes, Zhang happened to be walking in the woods when he encountered a crane fighting with a snake. The crane was jabbing at the snake with his long beak in straight angular strikes. The snake was able to avoid the crane’s strikes by changing its shape and position (staying very soft and resilient), slithering away, and quickly counterattacking while the bird was still committed to its original thrusts. Zhang gleaned from this that it would be possible for a weaker opponent to overcome a stronger one if he became soft and elusive. He incorporated this lesson into a new, softer version of a martial art and at the same time a health-promoting program. He reworked the original Forms of Shao Lin with a new emphasis on breathing and inner energy balance. It is reputed that he learnt and created the so-called “internal” boxing method. He then started a school which was known as the Wu-Tang School of Internal Boxing.

Anyway, Taiji’s essence principle, no doubt, has its roots in ancient Chinese philosophy, which included inherited Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. Some postures of style were inherited from Dao Yin of The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, the first important book for Traditional Chinese Medicine (about 206 B.C.–220 A.D.), and “Frolics of Five Animals” (tiger, deer, bear, monkey, and bird), created by the famous ancient Chinese doctor Hua Tuo (about 220–265 A.D.). Serious students of Taiji understand many of the terms and concepts used in traditional Chinese medicine, such as Yin–Yang, the Five Elements theory, Meridians, as well as the circulation of Qi as taught in the theories of Qigong, expect of historical martial art roots.

The theory is that Zhang San-Feng originated a soft style that combined existing combat techniques and other movements, primarily designed to increase the flow of Qi energy through the body, thus creating a form that was a physical manifestation of Taoist thought.

Going back even further in the third century, the ancestors of Taiji, the physician Hua Tuo  created a system of exercise to improve digestion and circulation, based upon the movements of animals and birds. The effect of this system was to move every part of the body. In the 6th century, Buddha Dharma visited the Shao Lin monastery, and developed a system of exercise for the monks, who were in poor physical condition due to too much meditation. This was known as the Eighteen-Form Luohan Exercise. Later, in the 8th century, this was developed into a 37-form “Long Kung-Fu,” which unlike other schools of Kung-Fu, was based upon a “soft” or internal approach, rather than a “hard” or external one.

created a system of exercise to improve digestion and circulation, based upon the movements of animals and birds. The effect of this system was to move every part of the body. In the 6th century, Buddha Dharma visited the Shao Lin monastery, and developed a system of exercise for the monks, who were in poor physical condition due to too much meditation. This was known as the Eighteen-Form Luohan Exercise. Later, in the 8th century, this was developed into a 37-form “Long Kung-Fu,” which unlike other schools of Kung-Fu, was based upon a “soft” or internal approach, rather than a “hard” or external one.

Modern non-violent Taiji as a form on its own, rather than being a part of martial arts, was developed much later, as the need for combat gradually decreased — although the Taiji practitioner is always aware that the forms are the same as those of combat, but slower. The Chen style contained jumps, leaps, and explosions of strength all within a circular path. The Yang style, formulated in the mid-l9th century, was softer, but was the most popular system.

“Taijiquan,” the original combat form of Taiji, means “Supreme Ultimate Fist,” but the word “Taiji” actually means one of the various changeable energy states or the situation of description, such as Huang Ji, Yuan Ji, or Wu Ji. “Taiji” was born of “Wu Ji,” at the moment between motion and still transforming, or separating into “Yin and Yang.” Nowadays the word “Taiji” is used as the name of a combat form or a fitness exercise. Unlike many other martial arts, which are “aggressive” or outward, the main principle of Taiji is that of a “soft” combat — absorbing the opponent’s aggressive energy and using it against him. This is a principle of Yin and Yang, a balance of opposites where “soft” is used to overcome “hard”, as described in the maxim “Use a force of four ounces to deflect that of a thousand pounds” or “Overcome a weight of a thousand carries by a force of four ounces.” Imagine an opponent twice your weight throwing a powerful punch — the Taiji adept would step back and absorb the punch by grasping the fist and pulling it past himself, using his opponent’s own forward energy and motion to overbalance the attacker. Or he might respond in any number of ways, always using the same principles.

So if we want to understand more about Taiji, we should know the essence of Chinese philosophy and culture as the following key points of view.

“Tao is action — only vague and intangible. Yet, in the vague and void, there is image, there is substance; within the intangible there is essence, there is marrow; this essence is real. Within this real being, there is validity, trust and information.”

“There is something evolved from the void and born before the making of heaven and earth. It is inaudible and invisible. It is independent and immutable. It is forever orbiting. It is the parent of all things of heaven and earth.”

Ancient Chinese philosophy considers that there is intangible energy called Qi (or Chi) which fills the universe, no matter if the object is large or small. It is an important part of Chinese culture. It suggests that Qi, a concept that is sometimes referred to as special energy, has features of energy, image, material, essence, information, and consciousness. Qi exists in the entire universe and is considered to be the basic unit of everything in the universe. It is the most essential of the substances making up the world, and it generated everything in the universe. Therefore, Qi is the root of a myriad of things, and everything has the spirit of Qi. It seems like the astronomical theory: before anything was created, the universe was in a chaos state, called Wu Ji; when it separated into Yin and Yang, it became the Taiji state (like Fig. 2), then created all things, i.e. “Tao engenders One, One engenders Two, Two engenders Three, Three engenders ten thousand things.” As a part of the universe, the human body is related to the universe as one union. It is believed that through systematic discipline (mental, moral, and physical) a human being can accumulate the vital bio-energy Qi and cultivate the potential ability to achieve longevity and intelligence.

Under this philosophy, Taiji was created and developed; it incorporates therapy and fitness, but always deals with the Qi or bioenergy principle. It conceives that a person has not only a physical body but also an intangible energy body — Qi system (meridian system, aura, etc.) enclosed in correlation with his spirit.

Based on this background, Taiji practitioners should understand this philosophy first, and then physically learn the series of postures combined with mind and breath training, called Xin Fa (the main principle of the mind–body practice technique). For most people, it is hard to understand the invisible Qi circulation in the body and the exchange of energy and message between the human body and the universe.

Simplified Tai Chi Practice Program

Principles of Taiji Practice

The main principle of Taiji originating from traditional Chinese philosophy is the holistic harmony and balance of Yin and Yang. The main purpose of Taiji practice in modern society is to achieve health benefit and longevity by balancing Yin and Yang in order to reach holistic harmony. Variations exist in how the principles of Taiji practice are stated, but the following principles are central to gaining more benefits, even beyond health purposes.

(1) “Stand like a balance and move like a wheel” (Wang Zongyue)

When you are standing you should be very stable, like a balance; when you are moving you should be very flexible, like a wheel. In this way of Taiji training, you can gradually get rid of rigidity and obtain flexibility in body, mind, and personality. Each body part moves like a wheel turning smoothly and stably, and any individual movement of a body part is accompanied and counterbalanced by the remaining movements of other parts. In each movement, every part of the body should be light, agile, and strung together, and each movement is slow but continually fluidic, endless but independent, and effortless but powerful.

(2)“Suspend the head, relax the shoulder and sink the elbow, and concentrate on the Dantian (Qi sinks in the Dantian located just below the navel in the abdomen)” (Wu Yunang)

Suspend the head to keep it straight and upward, as if there were an invisible thread fixed at Baihui (top of the head) and lightly lifting the head up throughout the neck and trunk. Only when you relax the shoulder and sink the elbow can you sink Qi in Dantian. This is the ideal way to harmonize the up side with the down side and “void soft” with “hard solid.” In this way, you can naturally relax the whole body and mind, and facilitate both the energy circulation inside the body and the energy exchange between the body and the universe.

(3)The waist is the commander of body movement

Subtle attention should always be paid to the waist so as to achieve real relaxation with extremely stable and flexible movement of the whole body, because the energy center (Dan Tian,  ) located just below the navel in the abdomen in the waist area of the body, and the whole body movements are initiated from the waist area. The waist movement directs the movement of other parts of the body like a commander and also leads the energy flowing to the whole body. It creates a real combination of movement and tranquility. Movement and tranquility always accompany each other. “It represents a balance, in which movement is characterized by tranquility and tranquility is represented by movement” (Wu Yunang).

) located just below the navel in the abdomen in the waist area of the body, and the whole body movements are initiated from the waist area. The waist movement directs the movement of other parts of the body like a commander and also leads the energy flowing to the whole body. It creates a real combination of movement and tranquility. Movement and tranquility always accompany each other. “It represents a balance, in which movement is characterized by tranquility and tranquility is represented by movement” (Wu Yunang).

(4)“Keep the mind calm when the body is moving” (Wu Yunang)

During Taiji practice, the body is moving but the mind is always calm. The mind is the general commander. Only when the mind is calm can it intelligently command the movement of the body. One draws the energy up from the earth through the Yong Quan ( , on the bottom of the foot), and the waist directs the flow of energy to the head and limbs like water flowing through a garden hose. In addition, a powerful mind may ensure a stable and peaceful body movement. On the other hand, skillful and natural body movement may improve mind power.

, on the bottom of the foot), and the waist directs the flow of energy to the head and limbs like water flowing through a garden hose. In addition, a powerful mind may ensure a stable and peaceful body movement. On the other hand, skillful and natural body movement may improve mind power.

(5)Taiji is also a special moving meditation

Taiji is considered a form of meditation with slow body movement, deep breathing exercise, energy guidance, and mind adjustment. It is sometimes called a moving meditation or Chinese moving yoga, because it integrates and coordinates the body, mind, energy or power or potency and conscious or subconscious function into a single whole. In particular, natural, deep, and even breathing is required and conscious and subconscious function is trained to be coordinated. “The mind is the director and the energy is the guider, so the mind governs the energy. The energy is the commander and the body is the soldier, so the energy dominates the body” (Wu Yunang).

In summary, “Applying the inside energy and power to the whole body, all the movements of bending or pulling and stretching or pushing of Taiji actually lead to continuous collecting and releasing of energy. It is a cultivation of energy through a closing or filling/opening or emptying activity to achieve health and longevity” (Chen Xin).

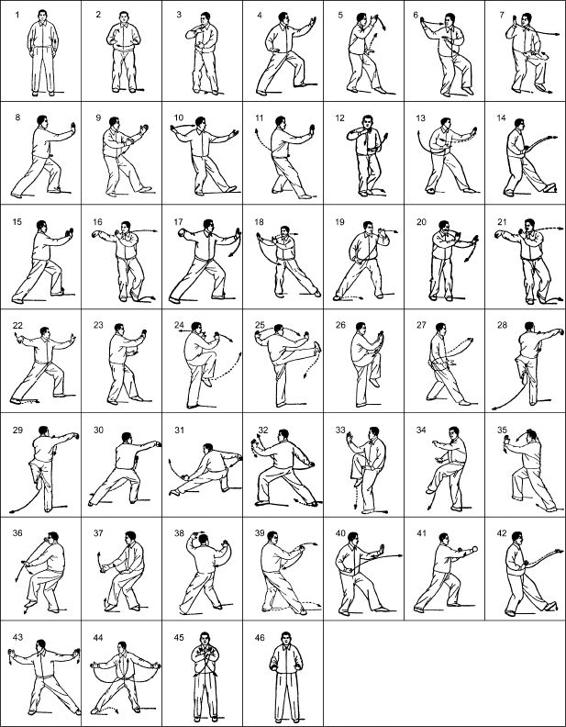

Twenty-Four-Form Style

Note:

(1)In the illustrations of 46 movements of 24-Form put together, the paths of the movements to be executed are indicated by arrows drawn in solid lines for the right hand and the left foot, and dotted lines for the left hand and the right foot.

(2)Movement directions are given in terms of the 12 hours of the clock. Begin by facing 12 o’clock, with 6 o’clock behind you, 9 o’clock on your left, and 3 o’clock at your right. Thus, a turn to 1 o’clock is one of 30° to the right, and a turn to 1:30 o’clock is one of 45°.

(3)An example illustration for the requirement of stand posture: head erect, torso straight, waist and hips relaxed, back leg extended naturally, Knee in line with toes.

Form 1: Commencing form

(1)Stand upright with the feet shoulder-width apart, the toes pointing forward, and the arms hanging naturally at the sides. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Hold the head and neck erect, with the chin drawn slightly inward. Do not protrude the chest or draw the abdomen in.

(2)Float the arms slowly forward to shoulder level, with the palms down (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(3)Bend the knees as you press the palms down gently, with the elbows dropping toward the knees. Look straight ahead.

Points to remember: Keep the torso erect and hold the shoulders and elbows down. The fingers are slightly curved. The body weight is equally distributed between the legs. While bending the knees, keep the waist relaxed and the buttocks slightly pulled in. The lower arms should be coordinated with the bent knees.

Form 2: Part the wild horse’s mane on both sides

(1)With the torso turning slightly to the right (1 o’clock) and the weight shifted onto the right leg, raise the right hand until the forearm is horizontally in front of the right part of the chest, while the left hand moves in a downward curve until it comes under the right hand, with the palms facing each other as if holding an energy ball (henceforth referred to as the “hold-ball gesture”). Move the left foot to the side of the right foot, with the toes on the floor. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Turn the body to the left (10 o’clock) as the left foot takes a step toward 8–9 o’clock, bending the knee and shifting the weight onto the left leg, while the right leg straightens with whole foot on the floor for a left “bow stance.” As you turn the body, raise the left hand to eye level with the palm facing obliquely up and the elbow slightly bent, and the lower right hand to the side of the right hip with the palm facing down and the fingers pointing forward. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(3)Repeat the movements in (1)–(2), reversing right and left (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Hold the torso erect and keep the chest relaxed. Move the arms in a curve without stretching them when you separate the hands. Use the waist as the axis in body turns. The movements in making a bow stance and separating the hands must be smooth and synchronized in tempo. When taking a bow stance, place the front foot slowly in position, with the heel coming first. The knee of the front leg should not be straightened, forming a 45° angle with the ground. There should be a transverse distance of 10–30 cm between the heels. Face 9 o’clock in the final position.

Form 3: The white crane flashes its wings

(1)With the torso turning slightly to the left (8 o’clock), make a hold-ball gesture in front of the left part of the chest, with the left hand on top. Look at the left hand.

(2)Draw the right foot half a step toward the left foot and then sit back. Turn the torso slightly to the right (10 o’clock), with the weight shifted onto the right leg and the eyes looking at the right hand. Move the left foot a bit forward, with the toes on floor for a left empty stance, with both legs slightly bent at the knee. At the same time, with the torso turning slightly to the left (9 o’clock), raise the right hand to the front of the right temple, with the palm turning inward, while the left hand moves down to the front of the left hip, with the palm down. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Do not thrust the chest forward. The arms should be rounded when they move up or down. Weight transfer should be coordinated with the raising of the right hand. Face 9 o’clock in the final position.

Form 4: Brush the knee on both sides

(1)Turn the torso slightly to the left (8 o’clock) as the right hand moves down while the left hand moves up. Then turn the torso to the right (11 o’clock) as the right hand circles past the abdomen and up to ear level with the arm slightly bent and the palm facing obliquely upward, while the left hand moves in an upward–rightward–downward curve to the front part of the chest, with the palm facing obliquely downward. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Turn the torso to the left (9 o’clock) as the left foot takes a step in that direction for a left bow stance. At the same time, the right hand draws leftward past the right ear and, following the body turn, pushes forward at nose level with the palm facing forward, while the left hand circles the left knee to stop beside the left hip, with the palm down. Look at the fingers of the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(3)Repeat the movements in (1)–(2), reversing right and left (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Form 5: Strum the lute

Move the right foot half a step toward the left heel. Sit back and turn the torso slightly forward, with the heel coming down on the floor and the knee bent a little for a left empty stance. At the same time, raise the left hand in a curve to nose level, with the palm facing rightward and the elbow slightly bent, while the right hand moves to the inside of the left elbow, with the palm facing leftward. Look at the forefinger of the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: The body position should remain steady and natural, with the chest relaxed, and the shoulders and elbows held down. Movement in raising the left hand should be more or less circular. In moving the right foot half a step forward, place it slowly in position, with the toes coming down first. Weight transfer must be coordinated with the raising of the left hand. Face 9 o’clock in the final position.

Form 6: Curve the arms on both sides

(1)Turn the torso slightly to the right, moving the right hand down in a curve past the abdomen, and then upward to shoulder level, with the palm up and the arm slightly bent. Turn the left palm up and place the toes of the left foot on the floor. The eyes first look to the right as the body turns in that direction, and then turn to look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Bend the right arm and draw the hand past the right ear, before putting it out with the palm facing forward while the left hand moves to the waist side, with the palm up. At the same time, raise the left foot slightly and take a curved step backward, placing down the toes first and then the whole foot slowly on the floor, with the toes turned outward. Turn the body slightly to the left and shift the weight onto the left leg for a right empty stance, with the right foot pivoting on the toes until it points directly ahead. Look at the right hand.

(3)Repeat the movements in (1)–(2), reversing right and left (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(4)Repeat the movements in (1)–(2) and (3).

Points to remember: The hands should move in curves when they are being pushed out or drawn back. While pushing out the hands, keep the waist and hips relaxed. The turning of the waist should be coordinated with the hand movements. When stepping back, place the toes down first and then slowly set the whole foot on the floor. Simultaneously with the body turn, point the front foot directly ahead, pivoting on the toes. When stepping back, the foot should move a bit sideways so that there will be a transverse distance between the heels. First look in the direction of the body turn, and then turn to look at the hand in front. Face 9 o’clock in the final position.

Form 7: Grasp the bird’s tail — Left style

(1)Turn the torso slightly to the right (11–12 o’clock), carrying the right hand sideways up to shoulder level, with the palm up, while the left palm is turned downward. Look at the left hand.

(2)Turn the body slightly to the right (12 o’clock) and make a hold-ball gesture in front of the right part of the chest, with the right hand on top. At the same time, shift the weight onto the right leg and draw the left foot to the side of the right foot, with the toes on floor. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(3)Turn the body slightly to the left, taking a step forward with the left foot toward 9 o’clock for a left bow stance. Meanwhile, push out the left forearm and the back of the hand up to shoulder level as if to fend off a blow, while the right hand drops slowly to the side of the right hip, with the palm down. Look at the left forearm (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Keep both arms rounded while pushing out one of them. The separation of the hands, the turning of the waist, and the bending of the leg should be coordinated.

(4)Turn the torso slightly to the left (9 o’clock) while extending the left hand forward, with the palm down. Bring up the right hand until it is below the left forearm, with the palm up. Then turn the torso slightly to the right while pulling both hands down in a curve past the abdomen (as if you were taking hold of an imaginary foe’s elbow and wrist in order to pull back his body) until the right hand is extended sideways at shoulder level, with the palm up, and the left forearm lies across the chest, with the palm turned inward. At the same time, shift the weight onto the right leg. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: While pulling down the hands, do not lean forward or protrude the buttocks. The arms should follow the turning of the waist and move in a circular path.

(5)Turn the torso slightly to the left as you bend the right arm and place the right hand inside the left wrist; turn the torso further (9 o’clock) as you press both hands slowly forward, with the palms facing each other and keeping a distance of about 5 cm between them, and the left arm remaining rounded. Meanwhile, shift the weight slowly onto the left leg for a left bow stance. Look at the left wrist.

Points to remember: Keep the torso erect when pressing the hands forward. The movement of hands must be coordinated with the turning of the waist and the bending of the front leg.

(6)Turn both palms downward as the right hand passes over the left wrist and moves forward and then to the right until it is on the same level as the left hand. Separate the hands shoulder-width apart and draw them back to the front of the abdomen, with the palms facing obliquely downward. At the same time, sit back and shift the weight onto the right leg, which is slightly bent, raising the toes of the left foot. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(7)Transfer the weight slowly onto the left leg while pushing the palms in an upward–forward curve until the wrists are for a left bow stance. Look straight ahead. Face 9 o’clock in the final position (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Form 8: Grasp the bird’s tail — Right style

Repeat the movements in (1)–(7), reversing left and right (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Form 9: Single whip

(1)Sit back and shift the weight gradually onto the left leg, turning the toes of the right foot inward. Meanwhile, turn the body to the left (11 o’clock), carrying both hands leftward, with the left hand on top, until the left arm is extended sideways at shoulder level, with the palm facing outward and the right hand is in front of the left ribs, with the palm facing obliquely inward. Look at the left hand.

(2)Turn the body to the right (1 o’clock), shifting the weight gradually onto the right leg and drawing the left foot to the side of the right foot, with the toes on the floor. At the same time, move the right hand up to the right until the arm is at shoulder level. With the right palm now turned outward, bunch the fingertips and turn them downward from the wrist for a hook hand, while the left hand moves in a curve past the abdomen up to the front of the right shoulder, with the palm facing inward. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(3)Turn the body to the left (10 o’clock) while the left foot takes a step toward 8–9 o’clock for a left bow stance. While shifting the weight onto the left leg, turn the left palm slowly outward as you push it forward with the fingertips at eye level and the elbow slightly bent. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Keep the torso erect, the waist relaxed, and the shoulders lowered. The left palm is turned outward slowly, not abruptly, as the hand pushes forward. All transitional movements must be well coordinated. Face 9 o’clock in the final position, with the right elbow slightly bent downward and the left elbow directly above the knee.

Form 10: Wave the hands like clouds — Left style

(1)Shift the weight onto the right leg and turn the body gradually to the right (1–2 o’clock), turning the toes of the left foot inward. At the same time, move the left hand in a curve the past abdomen to the front of the right shoulder, with the palm turned obliquely inward. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Turn the torso gradually to the left (10–11 o’clock), shifting the weight onto the left leg. At the same time, move the left hand in a curve past the face, with the palm turned slowly leftward, while the right hand moves slowly, turning obliquely inward. As the right hand moves upward, bring the right foot to the side of the left foot so that they are parallel and 10–20 cm apart. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(3)Repeat the movements in (1) and (2) (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji), reversing left and right.

Points to remember: Use your lumbar spine as the axis for body turns. Keep the waist and hips relaxed. Do not let your body rise and fall abruptly. Arm movements should be natural and circular, and follow waist movements. The pace must be slow and even. Maintain a good balance when moving the lower limbs. The eyes should follow the hand that is moving past the face. The body in the final position faces 10–11 o’clock.

(4)Repeat the movements in (1)–(2) and (3) two times.

Form 11: Single whip

(1)Turn the torso to the right (1 o’clock), moving the right hand to the right side for a hook hand while the left hand moves in a curve past the abdomen to the front of the right shoulder, with the palm turned inward. Shift the weight onto the right leg, with the toes of the left foot on the floor. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Repeat movements in (3) under Form 9 (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: The same as those for Form 9.

Form 12: High pat on the horse

(1)Draw the right foot half a step forward and shift the weight gradually onto the right leg. Open the right hand and turn up the palms, with the elbows slightly bent, while the body turns slightly to the right (10–11 o’clock), and raise the left heel gradually for a left empty stance. Look at the left hand.

(2)Turn the body slightly to the left (9 o’clock) position, pushing the right palm forward past the right ear, with the fingertips at eye level, while the left hand moves to the front of the left hip, with the palm up. At the same time, move the left foot a bit forward, with the toes on the floor. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Keep the torso erect, with the shoulders lowered and the right elbow slightly downward. Face 9 o’clock in the final position.

Form 13: Kick with the right heel

(1)Turn the torso slightly to the right (10 o’clock) and move the left hand, with the palm up, to cross the right hand at the wrist as you pull the left foot a bit backward, with the toes on the floor. Then separate the hands, moving both in a downward curve with the palms turned obliquely downward. Meanwhile, raise the left foot to take a step toward 8 o’clock for a left bow stance, with the toes turned slightly outward. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Continue to move the hands in a downward–inward–upward curve until the wrists cross in front of the chest, with the right hand in front and both palms turned inward. At the same time, draw the right foot to the side of the left foot, with the toes on the floor. Look forward to the right.

(3)Separate the hands, turning the torso slightly to 8 o’clock and extending both arms sideways at shoulder level with the elbows slightly bent and the palms turned outward. At the same time, raise the right knee and thrust the foot gradually toward 10 o’clock. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Keep your balance. The wrists are at shoulder level when the hands are separated. When kicking with the right foot, the left leg is slightly bent and the kicking force should be focused on the heel, with the ankle dorsal flexed. The separation of the hands should be coordinated with the kick. The right arm is parallel with the right leg, Face 9 o’clock in the final position.

Form 14: Strike the opponent’s ears with both fists

(1)Pull back the right foot and keep the thigh level. Move the left hand in a curve to the side of the right hand in front of the chest, with both palms turned inward. Bring both hands to either side of the right knee, with the palm up. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Set the right foot slowly on the floor toward 10 o’clock, shifting the weight onto the right leg for a right bow stance. At the same time, lower the hands to both sides and gradually clench the fists; then move them backward with an inward rotation of the arms before moving them upward and forward for a pincer movement that ends at eye level with the fists about 10–20 cm apart, and the knuckles pointing upward to the back. Look at the right fist (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Hold the head and neck erect. Keep the waist and hips relaxed and the fists loosely clenched.

Form 15: Turn and kick with the left heel

Repeat the movements in (1) of Form 13, but reversing right and left.

Form 16: Push down and stand on one leg — Left style

(1)Pull back the left foot and keep the thigh level. Turn the torso to the right (7 o’clock). Hook the right hand as you turn up the left palm and move it in a curve past the face to the front of the right shoulder, turning it inward in the process. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Turn the torso to the left (4 o’clock), and crouch down slowly on the right leg, stretching the left leg sideways toward 2 o’clock. Move the left hand down and to the left along the inner side of the left leg, turning the palm outward. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: When crouching down, turn the toes of the right foot slightly outward and straighten the left leg with the toes of the left foot in line with the right heel. Do not lean the torso too far forward.

(3)Turn the toes of the left foot outward and those of the right foot inward; straighten the right leg and bend the left leg onto which the weight is shifted. Turn the torso slightly to the left (3 o’clock) as you rise up slowly into forward movement. At the same time, move the left arm continuously to the front, with the palm facing right, while the right hand drops behind the back, still in the form of a hook, with bunched fingertips pointing backward. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(4)Raise the right knee slowly as the right hand opens into the palm and swings to the front past the outside of the right leg, with the elbow bent just above the right knee, and the fingers pointing up and the palm down. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Keep the torso upright. Bend the supporting leg slightly. The toes of the raised leg should point naturally downward. Face 3 o’clock in the final position.

Form 17: Push down and stand on one leg — Right style

Repeat the Form 16 movements, but reversing left and right.

Form 18: Work at shuttles on both sides

(1)Turn the body to the left (1 o’clock) as you set the left foot on the floor in front of the right foot, with the toes turned outward. With the right heel slightly raised, bend both knees for a half cross-legged seat. At the same time, make a hold-ball gesture in front of the left part of the chest, with the left hand on top. Then move the right foot to the side of the foot, with the toes on the floor. Look at the left forearm (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Turn the body to the right as the right foot takes a step forward to the right for a right bow stance. At the same time, move the right hand up to the front of the right temple, with the palm turned obliquely upward, while the left palm moves in a small leftward–downward curve, before pushing it out forward and upward to nose level. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Repeat (1) and (2), reversing right and left.

Points to remember: Do not lean forward, or raise the shoulders when moving the hands upward. The movements of the hands should be coordinated with those of the waist and legs. Keep a transverse distance. Face 2 o’clock in the final position.

Form 19: Needle at the sea bottom

Draw the right foot half a step forward, shift the weight onto the right leg, and move the left foot a bit forward, with the toes on the floor, for a left empty stance. At the same time, with the body turning slightly to the right (4 o’clock) and then to the left (3 o’clock), move the right hand down in front of the body, up to the side of the right ear, and then obliquely downward in front of the body, with the palm facing left and the fingers pointing obliquely downward, while the left hand moves in a forward–downward curve to the side of the left hip, with the palm down. Look at the floor ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Do not lean too far forward. Keep the head erect and the buttocks in. The left leg is slightly bent. Face 3 o’clock in the final position.

Form 20: Flash the arm

Turn the body slightly to the right (4 o’clock) and take a step forward with the left foot for a left bow stance. At the same time, raise the right hand with the elbow bent to stop above and in front of the right temple, with the palm turned obliquely upward and the thumb pointing down, while the left palm moves a bit upward and then pushes forward at nose level. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Keep the torso erect and the waist and hips relaxed. Do not straighten the arm when you push the left palm forward. The movement should be synchronized with the taking of the bow stance, with your back muscles stretched. Keep a transverse distance of less than 10 cm between the heels. Face 3 o’clock in the final position.

Form 21: Turn to deflect downward, parry, and punch

(1)Sit back and shift the weight onto the right leg. Turn the body to the right (6 o’clock), with the toes of the left foot turned inward. Then shift the weight again, onto the left leg. Simultaneously with the body turn, move the right hand in a rightward–downward curve and, with the fingers clenched into a fist, past the abdomen to the side of the left ribs with the palm turned down, while the left hand moves up to the front of the forehead, with the palm turned obliquely upward. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Turn the body to the right (8 o’clock), bringing the right fist up and then forward and downward for a backhand punch, while the left hand lowers to the side of the left hip with the palm turned down. At the same time, the right foot draws toward the left foot and, without stopping or touching the floor, takes a step forward, with the toes turned outward. Look at the right fist (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(3)Shift the weight onto the right leg and take a step forward with the left foot. At the same time, parry with the left hand by moving it sideways and up to the front, with the palm turned slightly downward, while the right fist withdraws to the side of the right hip with the forearm rotating internally and then externally, so that the fist is turned down and then up again. Look at the left hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(4)Bend the left leg for a left bow stance as you strike out the right fist forward at chest level, turning the palm leftward, while the left hand withdraw to the side of the right forearm. Look at the right fist (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Clench the right fist loosely. Follow the punch with the right shoulder by extending it a bit forward. Keep the shoulders and elbows lowered and the right arm slightly bent. Face 9 o’clock in the final position.

Form 22: Apparent close-up

(1)Move the left hand forward from under the right wrist and open the right fist. Separate the hands and pull them back slowly, with the palms up, as you sit back with the toes of the left foot raised and the weight shifted onto the right leg. Look straight ahead.

(2)Turn the palms down in front of the chest as you pull both hands back to the front of the abdomen and then push them forward and upward until the wrists are at shoulder level, with the palms facing forward. At the same time, bend the left leg for a left bow stance. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Do not lean backward or protrude the buttocks when sitting back. Do not pull the arms back straight. Relax your shoulders and turn your elbows a bit outward. The hands should be no farther than shoulder-width apart when you push them forward. Face 9 o’clock in the final position.

Form 23: Cross the hands

(1)Bend the right knee, sit back, and shift the weight onto right leg, which is bent at the knee. Turn the body to the right (1 o’clock) with the toes of the left foot turned inward. Following the body turn, move both hands sideways in a horizontal curve at shoulder level, with the palms facing forward and the elbows slightly bent. Meanwhile, turn the toes of the right foot slightly outward and shift the weight onto the right leg. Look at the right hand (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

(2)Shift the weight slowly onto the left leg with the toes of the right foot turned inward.Then bring the right foot toward the left foot so that they are parallel to each other and shoulder-width apart; straighten the legs gradually. At the same time, move both hands down in a vertical curve to cross them at the wrist first in front of the abdomen and then in front of the chest, with the left hand nearer to the body and both palms facing inward. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Do not lean forward when separating or crossing the hands. When taking the parallel stance, keep the body and head erect, with the chin tucked slightly inward. Keep the arms rounded in a comfortable position, with the shoulders and elbows held down. Face 12 o’clock in the final position.

Form 24: Closing form

Turn the palms forward and downward while lowering both hands gradually to the sides of the hips. Look straight ahead (Twenty-Four-Form style of Taiji).

Points to remember: Keep the whole body relaxed and draw a deep breath (exhalation to be somewhat prolonged) when you lower the hands. Bring the left foot close to the right foot after your breath is even. Walk about for complete recovery. Keep shoulders and elbows lowered and arms rounded. Face 10 o’clock in final position.

The Real Fitness and Therapy Principl on Tai Chi

Based upon the Western view of human anatomy and biology, a practitioner may only accept a human being as a solid body, which contains many systems and organs made up of different cells. However, according to the exploration of the human being’s potential ability, the TCM philosophy recognizes that a human being not only has a solid body but also an intangible energy body (meridian system, aura, and energy system).

We will now use an example to illustrate the way which the TCM philosophy looks at the body, and how it is different from the Western Philosophy. From Western understandings, according to the laws of dynamic and mechanical analysis, the organs inside the human body could not keep their regular position suspended in the cavity space of the body like blooming flowers or satellites in the universe, and would prolapse if they only relied on the integrity of muscles and tendons. So the question is: What force holds these organs in place all the time with their active functions? The TCM philosophy says that it is the bio-energy field that holds everything together in the proper place. Without the support of the energy field in the cavity space, organs would prolapse, and eventually wither. To TCM practitioners, the force of the energy field is as inherent as the force of the cosmic field that holds the stars suspended in the universe.

Everyone knows that all plants on the earth rely not only on the water and nutrition from the earth but also on the photosynthesis of chlorophyll in leaves reacting with the sunlight, the energy from the universe. The TCM philosophy believes that, like plants, human beings have a similar condition to exchange energy with the universe for vital life working by the subconscious mind.

This basic principle of Taiji is greatly influenced by The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, which says, “Train your mind in a quiet, calm and void state, keep your consciousness deep inside, how could you involve an illness?”, which means that human beings could prevent all diseases and achieve self-healing by balancing Yin and Yang, and improving the energy circulation of the body.

Within our solid body there are many spaces. In TCM, there are four big spaces: (1) the chest space between the spine and the chest ribs (called the Upper Jiao — a space area); (2) the upper abdomen space between the diaphragm and the navel (called the Middle Jiao); (3) the lower abdomen space between the navel and the pubis (called the Lower Jiao); (4) the back space between the spinal column and the organs, from the top of the head to the coccyx (called the Back Jiao). These spaces seem void, but are actually full of invisible energy fields like the universe space.

Western and Eastern medicine share the cell theory. The cells open to emit the energy out to space and close to absorb the energy from the space. The human body is like a universe, called the “small universe.” The cavity space is full of various kinds of energy, which congregate, collide, emerge, activate, circulate, and react to generate even newer energy. This is the human being’s intangible body, including the aura light, meridian system, inside-organ light, etc. The energy in the space forms an energy field like magnetic or gravity fields. The density and characteristics of the energy field influence the activities of cells and finally the health condition.

TCM has recognized that the energy field in the body space greatly influences the health condition of human beings. The influence is very simple and follows strictly the law of physics, diffusion theory. Whatever is at a higher concentration gradient will eventually diffuse into an area of a low concentration gradient.

If the density of the energy field in the space outside the organ is too high, the energy existing inside cells cannot be emitted to the space, because the law of physics would not allow that to happen. If the energy cannot be emitted out, the cells will not open properly, which in turn will cause stagnation of the energy and retention of the damp and heat inside the cells or organs. Further, this may cause the inflammation and/or even the mutation of the cells, eventually developing into cancers. If the density of the energy field in the space outside the organ is too low, it is easy for the cells to emit the energy from inside to the space, but difficult to absorb the energy from the space to inside. This will result in a lack of energy of the organ, showing weakness and low function of the organ.

Fortunately, the Taiji movements will influence the energy circulation of in the space of the body, thus regulating the density of energy fields and improving the health condition.

The function of cell energy follows the Entropy principle of thermodynamics. The energy stagnation inside cells is called “Positive Entropy,” which cannot be utilized. The cells can only emit this energy giving to other organs and benefiting them, and then the cells will empty themselves, which is called “Negative Entropy.” Only in this situation can the cells absorb the energy from outside and utilize it. This natural principle is completely similar to the Christian philosophy of to give and to receive. The more you give out, the more you will get.

Therefore, Life is simply the activation, circulation, and exchange of energy. If the movement of energy stops, the life will end. If the movement of energy is stagnating in some parts, these parts of the body will become diseased. The original reason for illness is not the infection of microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses, but energy stagnation. The infection of viruses is the result of energy stagnation for a period of time. For example, at the early stage of lung infection diseases there is no microorganism existing in the lung, but the density of energy in the chest space is abnormally high and the energy inside the lung cells is stagnating. After a while in this condition, microorganisms will appear. So TCM treats the patient holistically, with emphasis on preventing and self-healing strategy. In most cases, TCM does not directly attack the diseased organs or parts like allopathic medicine, but adjusts the whole body to reinforce the energy circulation in the diseased area.

From the point of view of martial arts, every posture of the original Taijiquan has probably some special meaning relating to fighting. But, in modern society, we concentrate more on the health purpose of Taiji. So, the following discussion emphasizes Xin Fa (the main principle of mind–body practice technique for mind training) of Dao Yin (using the mind to guide the Qi movement), related to fitness and therapy beyond the original meaning.

For example:

The Commencing Form requires relaxation of the whole body, breathing evenly, slowly, deeply, and smoothly, a peaceful mind, imagining your body being empty, loose, and melted with the universe, waiting for the energy to push your hands up and exchange the energy with the outside through the skin pores. It is important to get rid of burdens from the normal life and go into the special Taiji training state at the beginning.

The Hold-Ball gesture is one of the most basic gestures and appears many times in the whole Taiji routine. Holding a concentrated Qi ball between the hands in front of the abdomen (Lower Jiao) or chest (Upper or Middle Jiao) can strengthen the energy in the Dan Tian ( , CV 4 — in the middle of the lower abdomen) area which is a vital sea of human energy, or strengthen the energy in the chest by utilizing the outside energy field.

, CV 4 — in the middle of the lower abdomen) area which is a vital sea of human energy, or strengthen the energy in the chest by utilizing the outside energy field.

According to experiment and research, there are six meridian channels which start or end on the hands — which is connected with the whole body. There is a strong energy field around the hands. When the hands are moving through or staying beside some part of the body, this will influence the energy field of the body space. It will be stroked and changed.

During the Taiji movement, following the hand posture change, the energy function of corresponding organs will be adjusted. For instance, “Brush the Knee on Both Sides” (Form 4) will adjust the Qi circulation on the shoulders, neck, head, ears, and knees; “Grasp the Bird’s Tail” (Form 7) will adjust the Qi circulation of the Three Jiaos (Triple Energizer,  ) in the chest and the upper and lower abdomens, especially benefiting the heart and kidneys; “Single Whip” (Form 9) opens the Bai Hui (meridian point GV 20, at the top of the head) to exchange the energy with the universe and help the energy circulation of the liver; “Wave the Hands Like Clouds” (Form 10) is mostly beneficial to the head, face, and all organs on the face; “Push Down and Stand on One Leg” (Form 16) lets the energy of the universe connect and go through the body, especially benefiting the kidneys; “Cross the Hands” (Form 23) and “Closing Form” (Form 24) keep the energy storied in the body.

) in the chest and the upper and lower abdomens, especially benefiting the heart and kidneys; “Single Whip” (Form 9) opens the Bai Hui (meridian point GV 20, at the top of the head) to exchange the energy with the universe and help the energy circulation of the liver; “Wave the Hands Like Clouds” (Form 10) is mostly beneficial to the head, face, and all organs on the face; “Push Down and Stand on One Leg” (Form 16) lets the energy of the universe connect and go through the body, especially benefiting the kidneys; “Cross the Hands” (Form 23) and “Closing Form” (Form 24) keep the energy storied in the body.

Of course, the Taiji program has a holistic function for fitness and therapy and is not separate for special parts or organs, but we can select some individual postures for at-a-standstill training.

Some suggestions for the Taiji practitioner

For health purposes, we pay more attention to the fitness and therapy function of Taiji; the methods and requirements of Taiji practice are somewhat different from those of martial arts.

(1)After practicing for a while and becoming familiar with the routine of physical movements, you should slow down the movements gradually. For instance, “Simplified Taiji (24 forms)” usually takes five minutes, but now you are required to do it for half an hour or even longer. Only in this way can you have time to adjust your breath and put Xin Fa in it to train your mind. It looks very simple but is not easy, and one needs time and effort to practice and train.

(2)Read some books about Chinese culture and philosophy, especially Traditional Chinese Medicine. That will help you to understand the essence of Taiji Xin Fa and advance your understanding greatly.

(3)According to individual situations, you may select one or more postures as the stillstyle training or meditation as well as the Taiji practice.

(4)Last but not least, cultivate a your high moral standard of being responsible for society, and loving people and life. Only in this way can you keep your mind peaceful and insist on it for a lifetime to improve your practice gradually and obtain benefits continuously.

The benefits of practicing Tai Chi

Taiji, though having been the practiced for balancing mind and body to obtain physical and psychological health benefits in China for hundreds of years, has only recently gained the interest of researchers in Western countries as an alternative form of exercise. There is a steady increase in scientific research documenting the benefits of Taiji.

Literature reviews published between 1999 and 2001 began to offer conclusions based on reviews of clinical studies from a discipline or a focused clinical area perspective. Chen and Snyder reviewed the growing evidence assessing Taiji as a potential nursing intervention. As a result of their 1999 review, they concluded that Taiji practice had demonstrated benefits of balance improvement, fall prevention, cardiovascular enhancement, and stress reduction.

In a 2001 publication, Li et al. reviewed 31 topic-related articles, including both controlled experimental clinical trials and descriptive or case control studies, designed to assess either the physiologic response or the general health and fitness effect of Taiji practice. These authors concluded that Taiji is “a moderate intensity exercise that is beneficial to cardiopulmonary function, immune capacity, mental control, flexibility, and balance control; it improves muscle strength and reduces risk of falls in the elderly.” Fascko and Grueninger confirmed the conclusions of Li et al. after an extensive review of relevant literature assessing the effects of Taiji on physical and psychological health that included over 30 topic-related articles published before 2001.

In March 2004, Wang et al. published a systematic review of Taiji as a therapeutic intervention for chronic conditions. They reviewed 9 randomized critical trials, 23 nonrandomized controlled studies, and 15 observational studies. The authors’ conclusions included the following: Taiji has physiological and psychosocial benefits, and is safe and effective in promoting balance control, flexibility, and cardiovascular and respiratory function in older patients with chronic conditions.

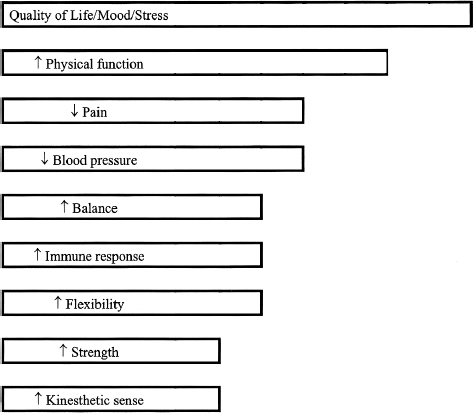

Most recently, a critical review by Klein et al. has offered an update on the current breadth and strength of research evidence regarding comprehensive therapeutic benefits of Taiji practice. Controlled research evidence has confirmed the therapeutic benefits of Taiji practice with regard to improving the quality of life, physical function including activity tolerance and cardiovascular function, pain management, balance and risk-of-fall reduction, enhancing immune response, and improving flexibility, strength, and kinesthetic sense. Figure 22.2 illustrates the distribution of therapeutic effects revealed in the 17 studies included in this critical analysis. Among the dependent variables examined in controlled research, improved indicators of quality of life were most often assessed and validated. Quality of life is a complex construct encompassing multiple and overlapping domains of life function. The effects related to general health and wellness, psychological, social, cognitive, and behavioral foci were grouped together under the collective subheading of “quality of life.” The second-most-frequently-studied beneficial effect was improved physical function.

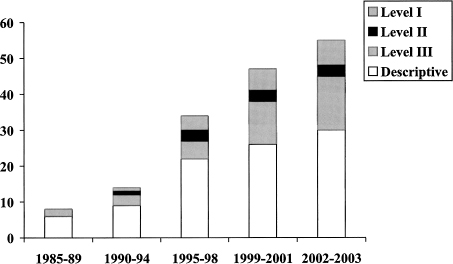

According to the critical analysis by Klein et al., of the more than 300 topic-related articles identified through an electronic search of the literature, more than 200 were judged to be original, topic-relevant scholarly or scientific reports. Of the more than 200 published reports examined, 17 controlled clinical trials were judged to meet a high standard of methodological rigor. A chronological descriptive analysis of dates of publications, the number, and the design rigor categorized as levels I–IV (controlled clinical trials, randomized clinical trials, observational case studies, pilot studies; and one-group trials) evidence reveals that the amount and strength of research evidence has increased exponentially in the past five years. Topic-related output within that time period has more than doubled the output for the previous 20 years (Summary of the frequency of outcome benefits of Taiji practice). The geographic distribution of publications examined includes scientific studies conducted in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Israel, China, South Korea, et al., showing that global clinical and research interest is evident within this body of published literature.

Sources: Medical and health-related English language publications from the past two decades, subcategorized by level of evidence (n = 154 clinically based articles). Level I — randomized clinical trials (randomized group assignment); Level II — controlled clinical trials (non-randomized group assignment); Level III — correlational and observational, including one group or case study with pretesting/posttesting; Descriptive — scholarly discussions and literature reviews.

Within the larger body of scientific reports and clinical studies including levels I–IV, a variety of clinical populations were studied. These included children with attention deficit, adults with cardiac dysfunction, and individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic back pain, osteoporosis, hemophilia, osteoarthritis, anky-losing spondylitis, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, head trauma, Parkinson’s disease, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and immune vulnerability.

A total of 1035 subjects participated in the 17 research studies included in the critical review by Klein et al. Demographic distributions consisted of at least 70% of the subjects being older adults, 60% or more were women, and more than 80% of the subjects represented non-clinical populations. Taiji intervention most often conformed to characteristics of the Yang style and most often included simplified forms modified from the traditional Yang style 108 (movements) forms. The lengths of Taiji intervention training ranged from 6 weeks to 12 months. Frequencies of supervised intervention ranged from one to three times weekly. Activity durations ranged from < 15 min to > 1 h per session.

The Taiji groups did so well in all these clinical trails that an article in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society recommended Taiji as a low-technology approach to conditioning that can be implemented at relatively low cost in widely distributed facilities throughout the community.

Beneficial effects on the cardiovascular and pulmonary system

Taiji exercise has recently gained the attention of Western researchers as a potential form of aerobic exercise. The aerobic capacity provides important information about cardiopulmonary function. The effect of Taiji exercise on aerobic capacity is important to know if clinicians want to recommend Taiji as an alternative form of aerobic exercise.

A study by Lai et al. found that elderly Taiji exercisers showed a significant improvement in oxygen (O2) uptake compared to an age-matched control group of sedentary elders. Lai and colleagues concluded that the data substantiated the practice of Taiji as a means of delaying the decline in cardiopulmonary function commonly considered “normal” for aging individuals. In addition, Taiji was shown to be a suitable aerobic exercise for older adults. Another study by Lai et al. substantiated that Taiji exercise is aerobic exercise of moderate intensity. The other cardiovascular study comparing elderly Taiji practitioners with a sedentary group also found that “the Taiji group showed 19% higher peak oxygen uptake in comparison with their sedentary counterparts.”

In a year-long clinical trial, individuals who had recently undergone coronary bypass graft surgery (n = 20) were non-randomly assigned to either a Taiji practice group or a home-based exercise group after completion of an aerobic cycling cardiac phase II exercise program. The Taiji group members were found to exercise at an intensity of 48–57% maximum heart rate range. Graded exercise tests performed before and after 1 year of intervention found that those in the Taiji group showed significant increase in the O2 peak (10% increase) and peak work (12% increase) as compared with the control group.

One intriguing finding of the current research has to do with evidence of conditioning effect at low training heart rates. Young et al. reported that, in a randomized control study, individuals exercising regularly performing Taiji with a mean exercising heart rate of 75 beats/min had a similar beneficial cardiovascular response related to decreased resting systolic blood pressure (mean change 7.0 mm Hg for resting systolic blood pressure) as compared with a comparison group who participated in a walking program at a mean heart rate of 112 beats/min (mean change 8.4 mm Hg for resting systolic blood pressure).

In another cardiac-related study, an 8-week randomized clinical trial (n = 126) was conducted to evaluate the effect of Taiji practice for individuals with recent myocardial infarcts. The results revealed that both the aerobic exercise group and the Taiji group had trends of reduced systolic blood pressure, but only the Taiji group showed trends of reduced diastolic blood pressure, suggesting that Taiji practice outcomes may be mildly superior to aerobic exercise programs for this clinical population.

The beneficial effects of Taiji on blood pressure and lipid profile and anxiety status have been shown in a randomized controlled trial of a Taiji group and a group of sedentary life controls (a total of 76 healthy subjects with blood pressure at high-normal, or stage I hypertension). After 12 weeks of Taiji training with a frequency of three times per week, as compared with the controls, the treatment group showed a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure of 15.6 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure of 8.8 mm Hg. The serum total cholesterol level decreased by 15.2 mg/dL and the high-density lipoprotein cholesterol increased by 4.7 mg/dL. Both trait anxiety and state anxiety were decreased. This study shows that under well-designed conditions, Taiji exercise training could decrease blood pressure, result in favorable lipid profile changes, and improve subjects anxiety status, suggesting that Taiji could be used as an alternative modality in treating patients with mild hypertension, with a promising economic effect.

The collective research evidence, with respect to cardiovascular rehabilitation applications, supports the view that Taiji practice is a safe, effective, low-intensity exercise regimen suitable for use as an exercise option with this vulnerable clinical population. The mechanism of effect is not fully understood, but the possibility of increasing aerobic capacity without stressing a compromised cardiac system is desirable. Although collaborating clinical research is needed, there is a theory-based rationale for generalizing these conclusions to pulmonary rehabilitation as well.

Balance improvement and fall prevention

One of the challenges faced by people with advancing age is decreased postural stability and increased risks of falls. There has been more interest and research over the last decade in using Taiji as an intervention exercise for improving postural balance and preventing falls in older people.

Improved balance is among the most commonly attributed benefits of Taiji practice. One of the earliest well-known studies addressing this effect is a correlation study. In an article published in 1992, Tse and Bailey reported balance abilities among experienced Taiji practitioners which were observed to be superior to balance abilities among sedentary subjects. This early work has become part of the justification for the belief that Taiji practice has potential use in fall reduction programs. The findings of a controlled clinical study by Tsang et al. indicated that even 4 weeks of intensive Taiji training is sufficient to improve balance control in the elderly subjects. These improvements were maintained even at followup 4 weeks afterward. Furthermore, the improved balance performance from week 4 on was comparable to that of experienced Taiji practitioners. A randomized controlled study by Jacobson et al. observed improved lateral balance stability in healthy volunteer adults (n = 24) after just 12 weeks of Taiji practice.

In a prospective controlled clinical study (n = 38), Lan et al. observed improved balance over time in the Taiji group as compared with controls. The subjects were older adults, and the study was conducted over a 12-month period. The mean frequency of practice was 4.6 times per week. The style of Taiji practiced in both studies was the 108 Yang form. Another randomized controlled trial showed that 6 months of low-intensity Taiji training could maintain the beneficial effects on balance and strength of 3 months of intensive balance and/or weight training. The subjects were 110 healthy community dwellers (mean age 80). Significant gains persisted after 6 months of Taiji training. Most recently, in a 2005 publication by Tsang et al., the results demonstrated that long-term Taiji practitioners had better knee muscle strength, less body sway in a perturbed single-leg stance, and greater balance confidence. Significant correlations among these three measures have uncovered the importance of knee muscle strength and balance control during a perturbed single-leg stance in older adults’ balance confidence in their daily activities.

Research evidence supporting clinical use of Taiji in the areas of fall prevention comes in major part from the well-known multiple-center FICSIT (Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies on Intervention Techniques) studies. The Atlanta group of the federally funded, prospective FICSIT study randomly assigned community-dwelling older adults (n = 200) to one of three groups: a 15-week course of Taiji exercises, computerized balance training, or education (control). The subjects were grouped in cohorts of 10–12. The Taiji groups met twice weekly, and the balance training and control groups met once weekly. Biomedical, functional, and psychosocial outcome variables were measured immediately and 4 months post-intervention. Although improvements in physiologic response to exercise were found in the Taiji group, the most cited finding of the followup study report is a 47% reduction in fall risk or delay of the next fall in the Taiji group.

Whereas the FICSIT studies suggested reduction in falls, a more recent randomized clinical trial (n = 163) conducted in Australia provides primary evidence. Barnett et al. randomly assigned community-dwelling elders known to have a risk of falling to either a control or a Taiji exercise group. The Taiji intervention consisted of weekly group instruction in Taiji combined with daily home practice. Physical performance and general health measures were assessed through repeated measures. After 1 year of Taiji practice, the experimental group was found to have a 40% reduction in falls. Furthermore, in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (n = 256), Li et al. concluded that improved functional balance through Taiji training is associated with subsequent reductions in fall frequency in older persons.

Recently, the potential benefits for healthy, younger cohorts and for wider aspects of health have also received attention. The study by Thornton et al. documented prospective changes in balance and vascular responses for a community sample of middle-aged (33–55 years) women (n = 34). Dynamic balance measured by the Functional Reach Test was significantly improved following a 12-week Taiji exercise program (three times per week), with significant decreases in both mean systolic (9.71 mm Hg) and diastolic (7.53 mm Hg) blood pressure, compared with sedentary control. The data confirm that Taiji exercise can be a good choice of exercise for middle-aged adults, with potential benefits for the ageing as well as the aged.

Pain management in chronic back pain and osteoarthritis

Taiji practice has been shown to be effective in pain management. Bhatti et al. reported preliminary findings of a randomized clinical trial (n = 51) investigating the efficacy of Taiji practice as a strategy to manage chronic pain. Adult subjects with a long-standing diagnosis of chronic back pain were assigned to either a control group or a Taiji exercise group. The study results after 6 weeks of Taiji practice revealed significant reductions in the average, lowest, and worst pain experienced in the last week, measured on a visual analog scale, and self-reported improvements in mood.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis in the United States. It causes functional limitations and pain that worsen an individual’s quality of life. Reducing the pain associated with OA is an important consideration in managing OA. In a randomized clinical trial of adults with lower limb OA (n = 33), Hartman et al. found that after 12 weeks of twice-weekly supervised exercise sessions, subjects in the Taiji group reported significant increases in self-efficacy for arthritis symptoms and improved satisfaction with general health as compared with controls. Similarly, Adler et al. demonstrated, in a pilot study, that pain intensity scores for individuals (n = 16) with chronic arthritis pain decreased as compared with controls. The experimental intervention employed was a 10-week program of once-weekly supervised Taiji exercise.

The safety of Taiji for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients was evaluated in a study (n = 55) by Kirsteins et al. RA patients, who received 1 h of Taiji instruction once and twice a weeks for 10 weeks in two separate studies, showed no deterioration in their clinical disease activities compared with the corresponding controls. No significant exacerbation of joint symptoms in the use of this weight-bearing form of exercise was observed. Taiji exercise appears to be safe for RA patients and may serve as an alternative to their exercise therapy and part of their rehabilitation program.

Improved flexibility, strength, and kinesthetic sense

In physical rehabilitation, there is agreement that a relationship can exist between a reduction in impairment and an improvement in function. Variables such as flexibility, strength, and kinesthetic sense are impairments that are associated with the complex construct of physical function. Evidence, generated through controlled clinical research, has demonstrated the beneficial effects of Taiji practice on these three variables. In addition to improvements in lateral body stability related to balance, Jacobson et al. found significant improvements in leg extensor strength and kinesthetic sense in healthy subjects after 12 weeks of Taiji. Sun et al. observed lower resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure and increases in shoulder and knee flexibility in older adults who participated in a 12-week program of Taiji exercises, as compared with randomly assigned controls. In a prospective controlled trial (n = 36), Chen and Sun observed increased flexibility measured using a sit and reach box. The Taiji intervention employed in the latter study consisted of the Yang-style 24-movement form and was conducted over 16 weeks at a frequency of twice-weekly classes. Such demonstrations of beneficial changes in physical variables, often addressed as goals of physical rehabilitation, make Taiji practice an exercise intervention option with potential to achieve improved flexibility, strength, and kinesthetic sense.

Potential immune response effects

A potential immune response effect of Taiji practice is a frequent claim of Taiji enthusiasts. Preliminary evidence of this phenomenon was provided in a two-group study of Taiji practitioners who reported six years or more of regular Taiji practice. Xusheng et al. found positive changes in humoral activity attributed to a single episode of practice, and indications of humoral immunity associated with long-term Taiji practice.

Clinical evidence to assess the effect of Taiji practice on immune response within novice Taiji practitioners is just emerging. Both the incidence and the severity of herpes zoster (shingles) increase markedly with increasing age in association with a decline in varicella zoster virus (VZV) specific cell-mediated immunity. In a randomized clinical trial (n = 36), Irwin et al. exposed older adults with no previous Taiji experience to 15 weeks of practice at a frequency of three times a week. The results revealed a nearly 50% increase in VZV-specific, cell-mediated immunity in the Taiji group as compared with demographically similar, wait-list controls. In addition, Taiji was associated with improvements in physical health functioning, with the greatest effects in those older adults who had impairments of physical status at entry into the study. Evidence of this enhanced immune effect suggests clinical applications for the elderly, who naturally experience some decline in immune response, and for immune-suppressed individuals. This is an under-researched area with great potential.

Psychological benefits

Taiji augments the exercise effects through the use of both mental concentration and relaxation of tension, which are thought to benefit emotional states. The psychological benefits of Taiji practice have been shown in a number of studies and reviews.